Unity Catalog and Basic Objects

Navigating your catalogs, schemas, tables, and more in the Databricks Unity Catalog.

After providing some simple code for creating a set of basic data objects to work with, we should explore the Unity Catalog and how Databricks arranges data objects for users. Despite Databricks’ background as a tool for leveraging data science and machine learning, it has been introducing more and more database and business intelligence functionality, and I imagine the majority of people who come to Databricks for the first time are used to traditional database paradigms that you might find in SQL Server or Oracle.

So what is the Unity Catalog?

According to it’s own website, Unity Catalog is: “Industry’s1 only universal catalog for data and AI”.

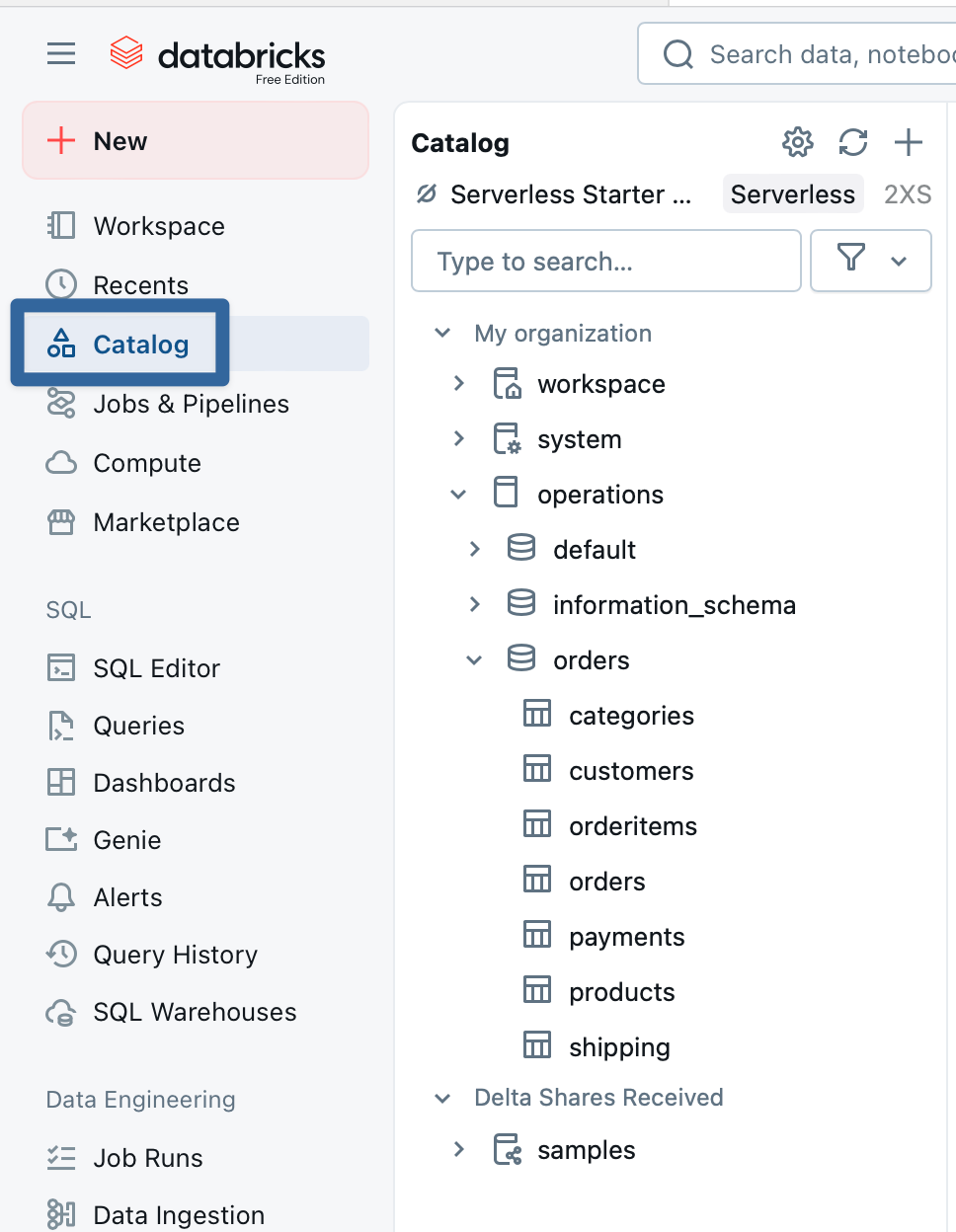

A (now) open-source project developed by Databricks, it is the ‘glue’ that connects your data assets2 and allows you to navigate and peruse them. When you click on the ‘Catalog’ navigation option…

…you are now navigating using the Unity Catalog3.

If you are coming to Databricks from a traditional business intelligence or data warehouse background, you’re likely most interested in finding your databases.

Technically, there isn’t a “database” in Unity Catalog; these things…

…are actually “schemas” (despite having an icon that looks suspiciously like a database). For most users of Databricks, the data hierarchy looks like this:

Catalogs

Schemas

Tables / Views

Columns

Essentially, ‘schemas’ are what you previously knew as ‘databases’. ‘Catalogs’ let you group a bunch of schemas together.

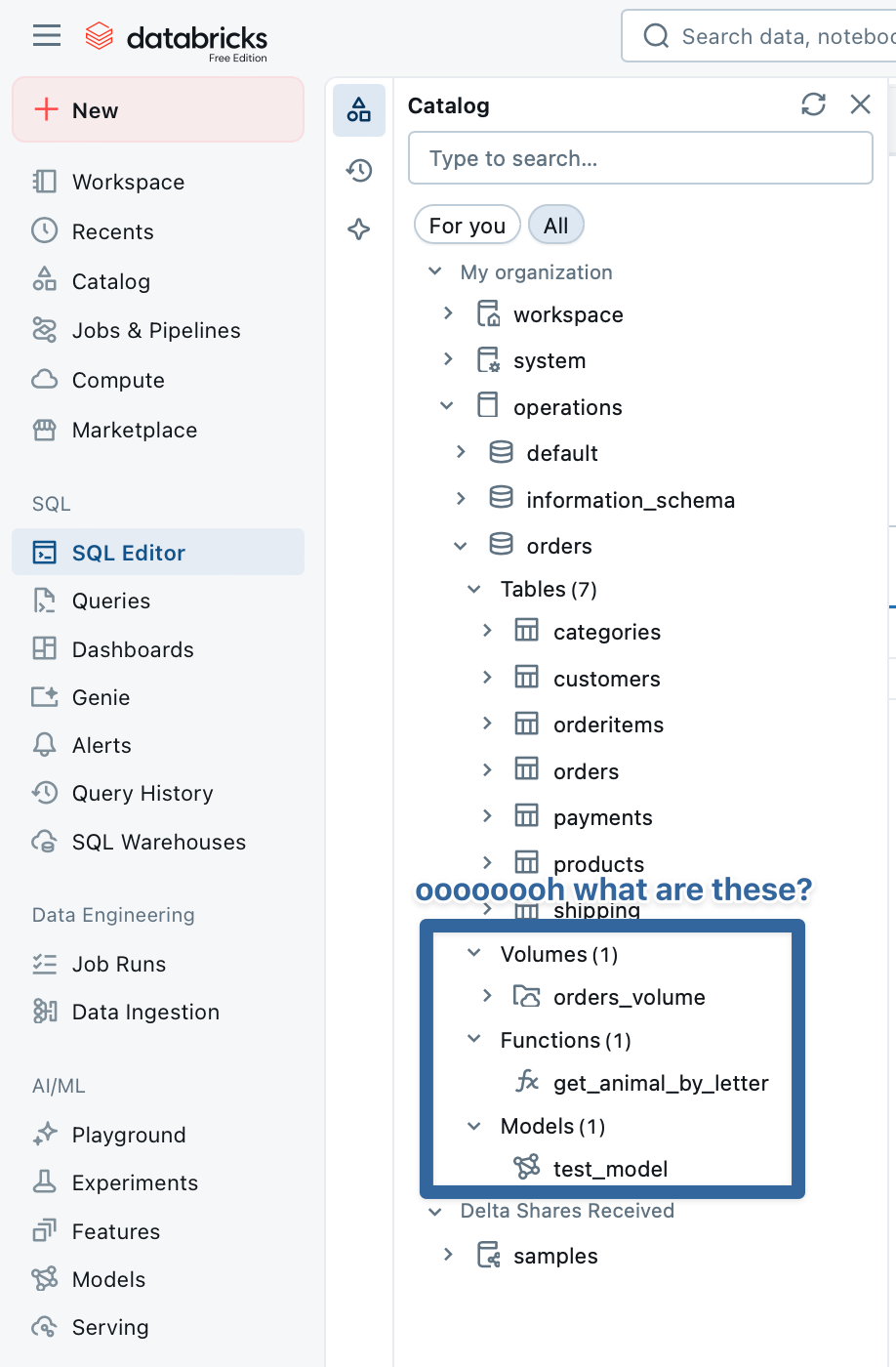

There are also some extra objects you can have in your schemas:

Databricks Volumes are repositories where you can upload files, such as csvs and text files4, for use with Databricks. A neat trick is that if you upload a csv or text file, you can actually just query that file directly instead of having to load it into a table first:

SELECT * FROM csv.`/Volumes/catalog_name/schema_name/volume_name/data.csv`Neat!5

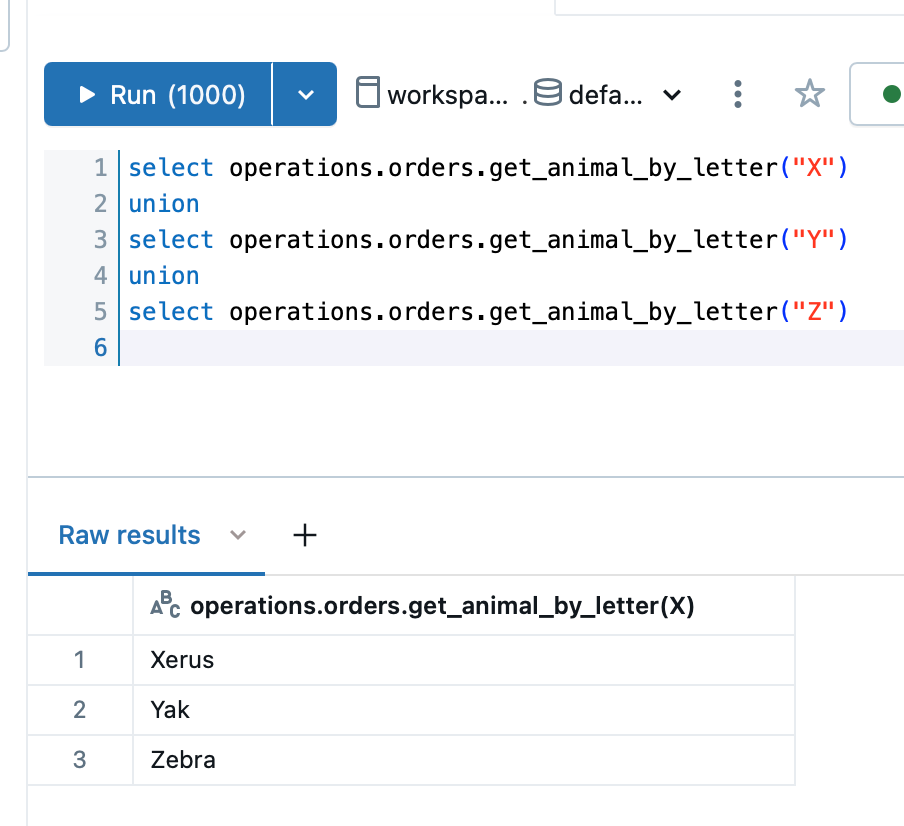

Databricks Functions are stored user-defined functions. While there is an ever-growing heap of built-in functions in Databricks, sometimes you need to build your own; this is useful if you have special field-level security (like masking or XXXXX on sensitive data) or row-level-security (e.g. “users can only see rows where column [username] matches”). This is where they’re stored, schema-by-schema6.

Databricks Models are machine learning models which can be accessed both via Unity Catalog or via the ‘AI/ML’ section of the navigation side-menu. Data scientists and ML practitioners can use Unity Catalog to store models they’ve created and tuned, and users can gain access.

So with these additions in mind, our basic hierarchy now looks like this:

Catalogs

Schemas

Tables/Views

Columns

Volumes

Files

Functions

User-defined functions

Models

machine learning models

Eagle-eyed viewers will note there’s something called ‘Delta Shares Received’ in my screenshots. This is a way to share data across Unity Catalog metastores.

What the heck is a metastore?

A metastore is the thing that keeps track of your data assets - catalogs, schemas, tables, permissions, etc. If that sounds suspiciously like the Unity Catalog, then you’re not wrong - the Unity Catalog is a type of metastore. Databricks used to employ Apache Hive metastores before developing their own Unity Catalog, and then releasing it into the wild7. In commercial Databricks, you can have multiple metastores, but each Workspace8 can only use one metastore. But if you want to/need to share data to beyond the metastore in the Workspace you’re using, including sharing data with another Databricks customer (or accessing data from another Databricks customer…or even a data broker!), you can set up a ‘Delta Share9’ and define which objects should be visible to the external users/other Workspace/other metastore. And in the screenshot above, Databricks themselves have shared the ‘samples’ catalog with all Databricks Free Edition users.

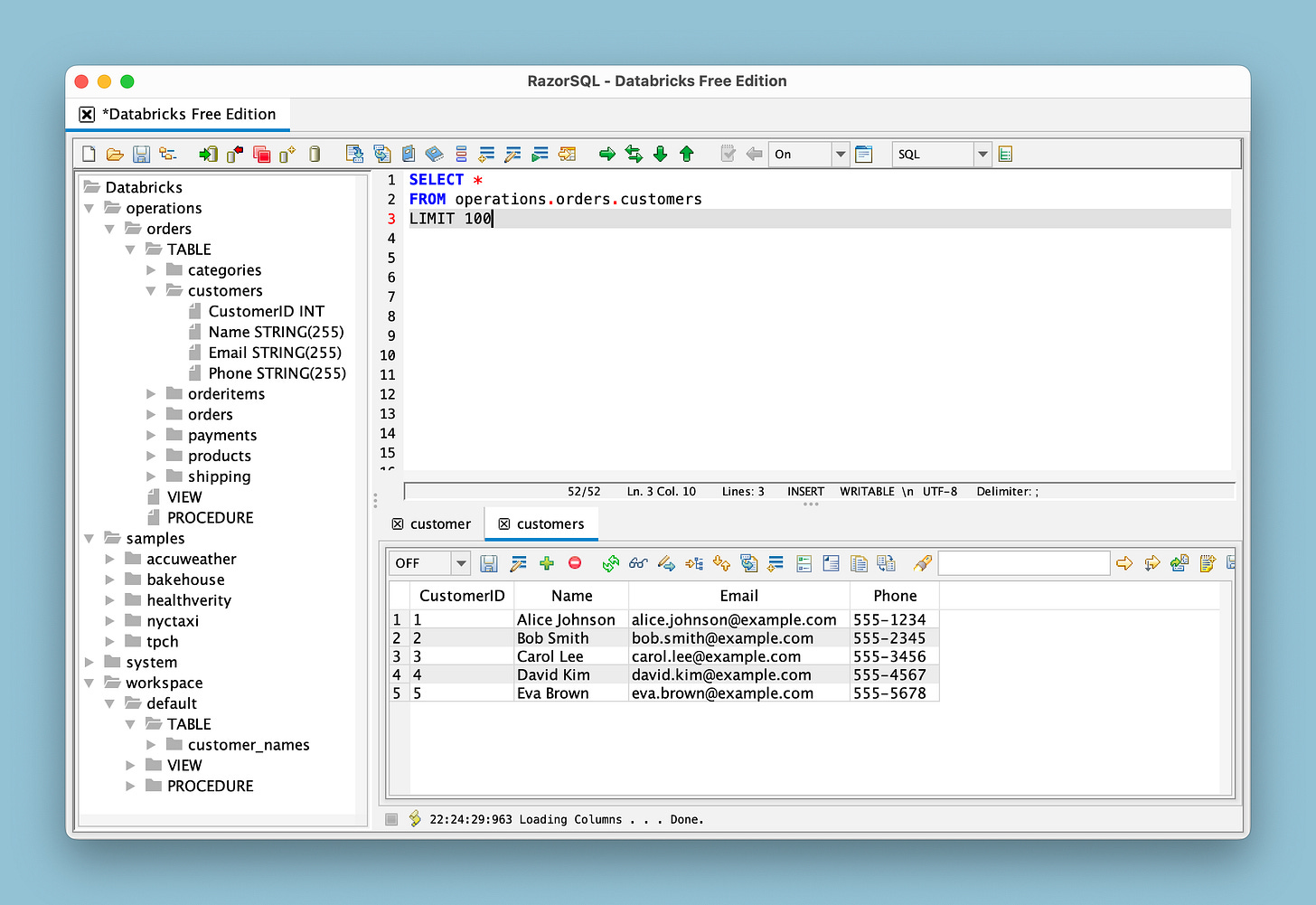

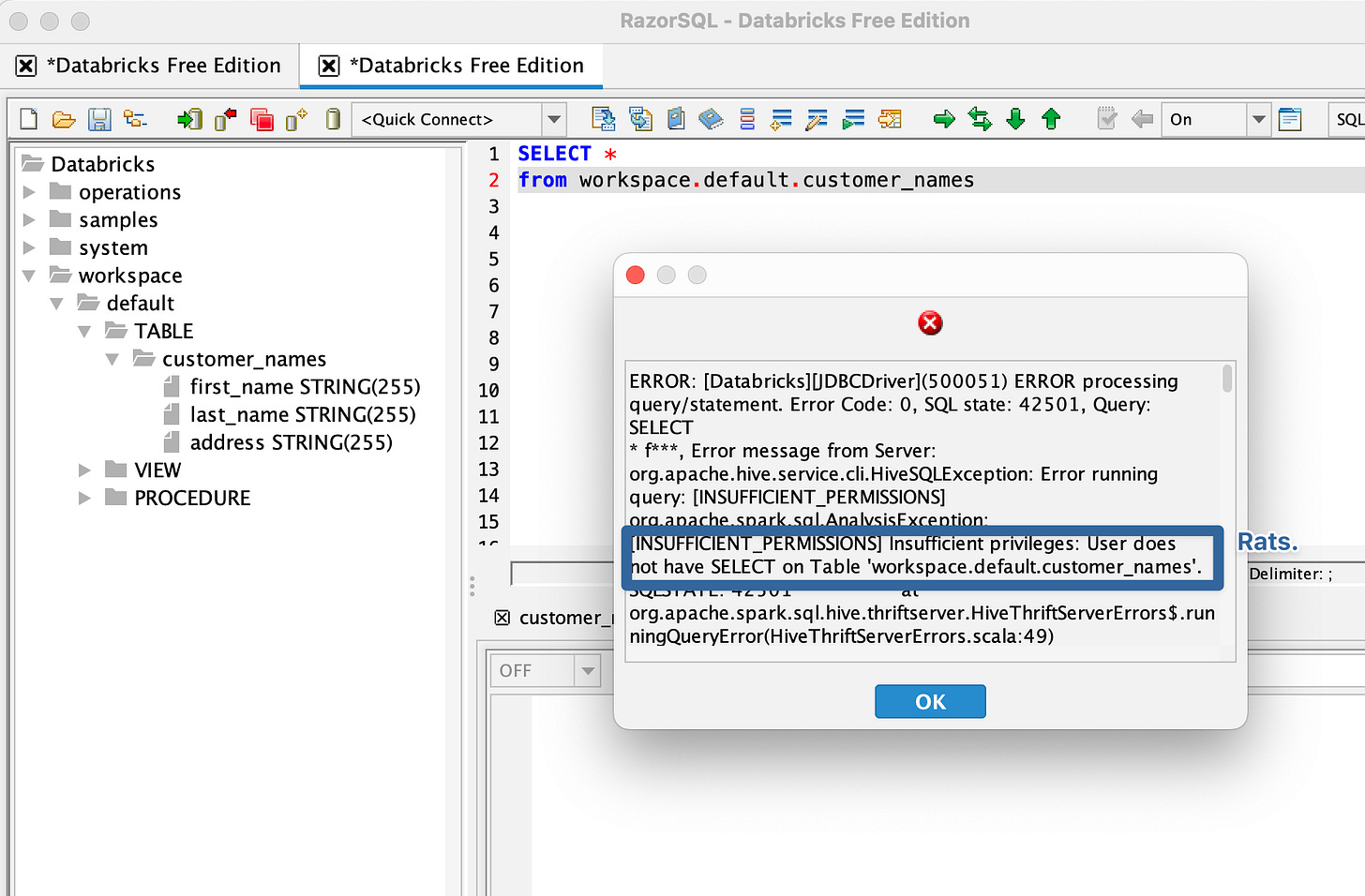

You should now be familiar with how Databricks and the Unity Catalog arrange your data for perusal. Even connecting to your data via a SQL IDE (which we’ll go over soon), you can see the same catalog → schema → table hierarchy:

In the screenshot above, you can see the ‘operations’ catalog I’ve been using as my example, as well as the ‘sample’ Delta Share I commented on above10. Your IDE may show arrangement or other differences, but you can see a query executed using our operations.orders.customers table.

There is plenty more to cover in Unity Catalog - we haven’t even touched metadata like comments or permissions - but this should be plenty to get Databricks newcomers on their way!

Something about this slogan bugs me. “Industry’s”. Using a zero article, bare genitive noun phrase is obviously common in slogans, headlines, and buttoned-up corporate policies. But this one irks me, although I won’t get it into it because I already mocked it in the screenshot caption. I will say, though, saying and thinking about the word “industry” has sparked a bout of semantic satiation more rapidly for me than any word before it. Industry. Industry. Induuuuustry. Industryyyyyyy. Industry.

(and tangential assets like Delta Shares, External Locations, Connections, Clean Rooms, Certificates, etc., all of which we’ll worry about another time)

And while I already went on a big fussy baby tantrum about it, it’s worth noting that Databricks - like Snowflake and Tableau and Microsoft and every other company working with metaphors for their software - reuses terms to the point of abusing their users confusion, one of which is ‘catalog’. You click on [Catalog] to open a window called ‘Catalog’ which uses the Unity Catalog to peruse your catalogs.

I could rant about that again. Or I could acknowledge that despite having personal computers in our lives since the 1970s, and those computers being an indispensable part of our lives since the late 1990s, and having them shrink in size and accompany us in all aspects of daily life since the mid-2000s, and now being able to have real-time conversations with them in natural language, we still wriggle through a series of fraught metaphors for actually interacting with them. For instance, I recall the first time I tried to help my mother navigate a brand-new bondi blue iMac. From the outset we had issues - it’s easy to forget that even the simplest metaphorical concepts that GUIs employ take some real learning, some real mental translations. To wit: after the iMac welcomed us, I tried to get my mother to ‘click’ on a folder, ‘open’ a ‘document’, and place something on the ‘desktop’. To her, all of this sounded like gibberish. In real life, we don’t click on manila folders, we open them, usually left to right in Western society. We don’t open documents, we simply pick them up and read them, who ‘opens’ a document? You might open a letter, I guess? (Technically, you open the envelope. Technically.) And to place something on the ‘desktop’, well, that sounds like something I’d do when I’m tired of physically holding the document, I’d lay it down there and just lean over and give it a read.

Similar to how we can seamlessly translate everyday metaphors such as “he’s fishing for compliments” or “she’s a night owl” or “they’re drowning in paperwork”, we’ve adopted and learned how to navigate ‘folders’ and ‘run programs’. But my mother struggled, at least initially, with these metaphors, just as a non-native speaker of English might struggle with “fishing for compliments”, “night owl”, “I’m swamped” or “I could use another set of hands”. (I wish I could put footnotes in my footnotes, because if I could, I’d cite 猫の手も借りたい, my favorite Japanese colloquial metaphor. “I want to borrow cat’s hands.” And you, as a ((likely)) non-native speaker of Japanese who has never been exposed to these everyday metaphors, doesn’t quite know what it means or when you would use it. To prove my point. But since I can’t put footnotes in footnotes, I’ll just use parenthesis.)

(Also, if I wanted to, and believe me I do because I’m pedantic ((OBVIOUSLY)) and like to hear myself type ((ALSO, OBVIOUSLY)), I could delve into the really wanky semiotic ideas behind the signifier and the signified, because really, when I look at a computer or a TV or an iPad or my Android phone, what I’m looking at are photons lighting up pixels arranged in a pattern that I’ve been trained to recognize. When pets look at a TV screen, are they actually watching a show or movie? They might be attracted by the sounds or the light pattern, but do they actually mentally translate the pattern of lights on the 2D screen to a meaningful image? If I hold up a painting to my dog, does he interpret it as a beautiful forest landscape or does he just see blobs of green and blue ((well, actually, yellow-green and blue-violet))? Another example: if I asked you “QUICK WHAT IS THAT METAL HEXAGONAL PLAQUE IN A MOSTLY RED HUE WITH WHITE GLYPHS?!” versus “Is that a ‘Stop’ sign?”

Encountering the object above, a baby or an interstellar alien visitor would at best recognize a metal hexagon, mostly red. You and I would slow our car to a stop.

Luckily for you, we don’t have time to dig into this kind of dull semiotics nonsense right now.)

And to finally tie this in a bow (another metaphor!) - Databricks already stumbled into a strained battleground of metaphors, cluttered with ‘data warehouses’ and ‘data marts’ and ‘data lakes’, to which they pitched their (honestly somewhat silly sounding) concept of a ‘data lakehouse’. As with all successful ventures, as the Databricks platform expands and introduces new features, they have to contend with what to name their stuff. The word ‘catalog’ happens to be the most egregious, and I often find myself coaching frustrated new users who just want to see their damn data already. So I just kinda wish Databricks would invest in a thesaurus.

You can even upload init_scripts for use with interactive clusters and job clusters, although that’s beyond the scope of this basic introduction.

I guess now is as good a time as any to go over this. Look closely at the code I posted:

SELECT * FROM csv.`/Volumes/catalog_name/schema_name/volume_name/data.csvIf you haven’t worked with MySQL or Databricks before, you might not know; I sure didn’t. These are not single quotes. These symboles: `, are called ‘backticks’.

If you’d like to take a simple udf for a spin, the one I used in my screenshots, ‘get_animal_by_letter’, is this:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION operations.orders.get_animal_by_letter(letter STRING)

RETURNS STRING

RETURN CASE UPPER(letter)

WHEN 'A' THEN 'Antelope'

WHEN 'B' THEN 'Bear'

WHEN 'C' THEN 'Cat'

WHEN 'D' THEN 'Dog'

WHEN 'E' THEN 'Elephant'

WHEN 'F' THEN 'Fox'

WHEN 'G' THEN 'Giraffe'

WHEN 'H' THEN 'Horse'

WHEN 'I' THEN 'Iguana'

WHEN 'J' THEN 'Jaguar'

WHEN 'K' THEN 'Kangaroo'

WHEN 'L' THEN 'Lion'

WHEN 'M' THEN 'Monkey'

WHEN 'N' THEN 'Newt'

WHEN 'O' THEN 'Owl'

WHEN 'P' THEN 'Penguin'

WHEN 'Q' THEN 'Quokka'

WHEN 'R' THEN 'Rabbit'

WHEN 'S' THEN 'Snake'

WHEN 'T' THEN 'Tiger'

WHEN 'U' THEN 'Urial'

WHEN 'V' THEN 'Vulture'

WHEN 'W' THEN 'Wolf'

WHEN 'X' THEN 'Xerus'

WHEN 'Y' THEN 'Yak'

WHEN 'Z' THEN 'Zebra'

ELSE 'Unknown'

END;

This function, when passed a capital English letter, will return one of the animals listed:

SELECT operations.orders.get_animal_by_letter("A")A fun project I hope to take for a spin someday is dumping a bunch of data into S3 and then downloading the Unity Catalog repo and trying to get my own copy of it working.

I have a subjective definition of the word ‘fun’.

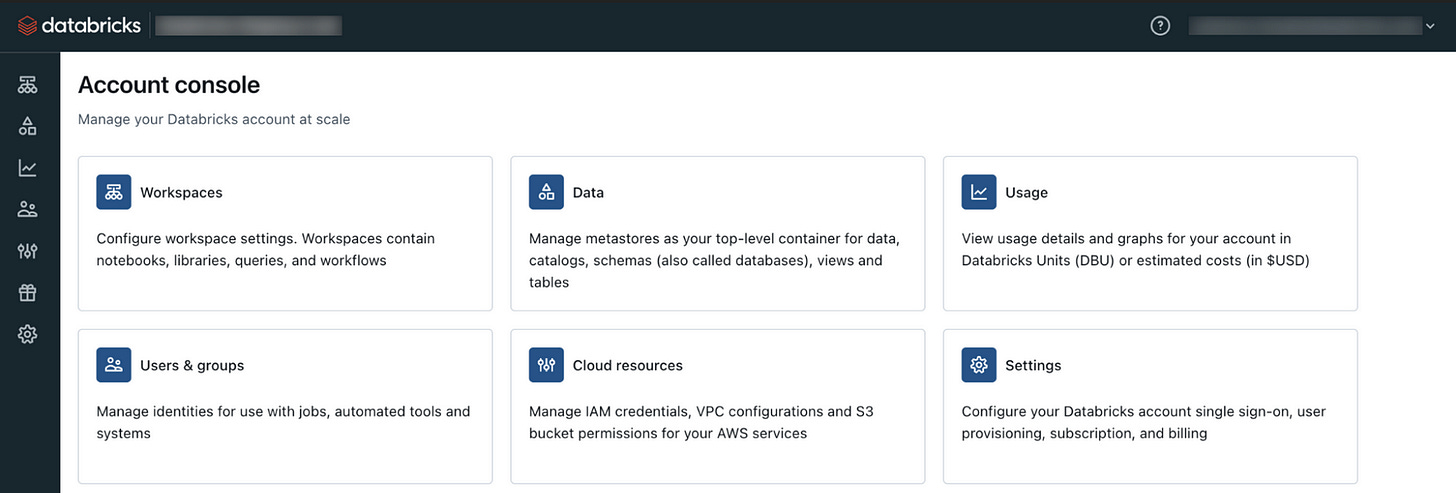

Another term abused by Databricks, but I’ve already tuckered myself out over the topic in a different footnote. I will say - in Databricks Free Edition you only get one Workspace, which means you only get one metastore, and you have no way to create more. In the Databricks Commercial or Gov editions, there is an ‘Account Console’ which allows you to create multiple Workspaces and set up multiple metastores.

However, since we’re using Free Edition, and this blog is hoping to lean more towards using Databricks instead of administering Databricks, we’ll just leave it at that for now.

Why is it called ‘Delta Share’ instead of ‘Unity Catalog Share’ or ‘Metastore Share’? Essentially, when you write a table to a schema in Databricks, what you see is a table in the Unity Catalog, but what is actually stored on a disk somewhere is Parquet files tracked by a delta log. So, like, the data itself is written to Parquet files, this extra file called a ‘delta log’ keeps track of which data is in which file, and Unity Catalog interprets this to show you schemas and tables. These Parquet and delta log files are part of a data repository called Delta Lake. So Unity Catalog and Delta Lake work together:

Unity Catalog manages metadata, governance, and access

Delta handles storage, consistency, and updates.

When, in Unity Catalog, you actually determine which catalogs, schemas, and tables you want to share with another Databricks customer, what they see looks like the same Unity Catalog catalogs, schemas, and tables…but they’re actually accessing the data from your Delta Lake. Hence, ‘Delta Share’.”

(Okay, so, that last sentence was a bit simplified - when you set up a Delta Share, your partners aren’t actually accessing data from your Delta Lake. That would be a crazy security concern. Instead, there’s a protocol called Delta Sharing, and Databricks themselves have explained it in plainspeak right here.)